This is a continuing series on the “Jargon-Free security model.” In part I, we briefly introduced the model. In part II, we covered the foundational capability, “Visibility.” Part III covered the other half of effective Information Security, “Control.” Part IV talked about “Compliance” as essential busywork that you should manage as cheaply as possible. In this part, we discuss Innovation: getting ready for the future.

Time is a relentless enemy, and your current “state of the art” controls may be inadequate in a short time. To ensure that you have the tools to meet the challenges of the future, you need a structured program to evaluate existing and emerging technologies that may be candidates for future security capabilities in your security program.

If you’re not failing, you’re not trying hard enough.

By definition, innovation carries a lot of risks. Of all the tools and techniques in the world, only a small minority of them will work in your enterprise, and the only way to find out which ones work is by trying them. Most of them won’t, but that failure is the price of innovation. As Thomas Edison said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Since these investigations, successful or not, take time and resources, you should manage them to maximize the chance of success. This is more art than science, but some structured thinking can help you improve the odds, and more importantly, justify the investment to your executive team. The key is to understand how innovation delivers business value.

How innovation delivers business value

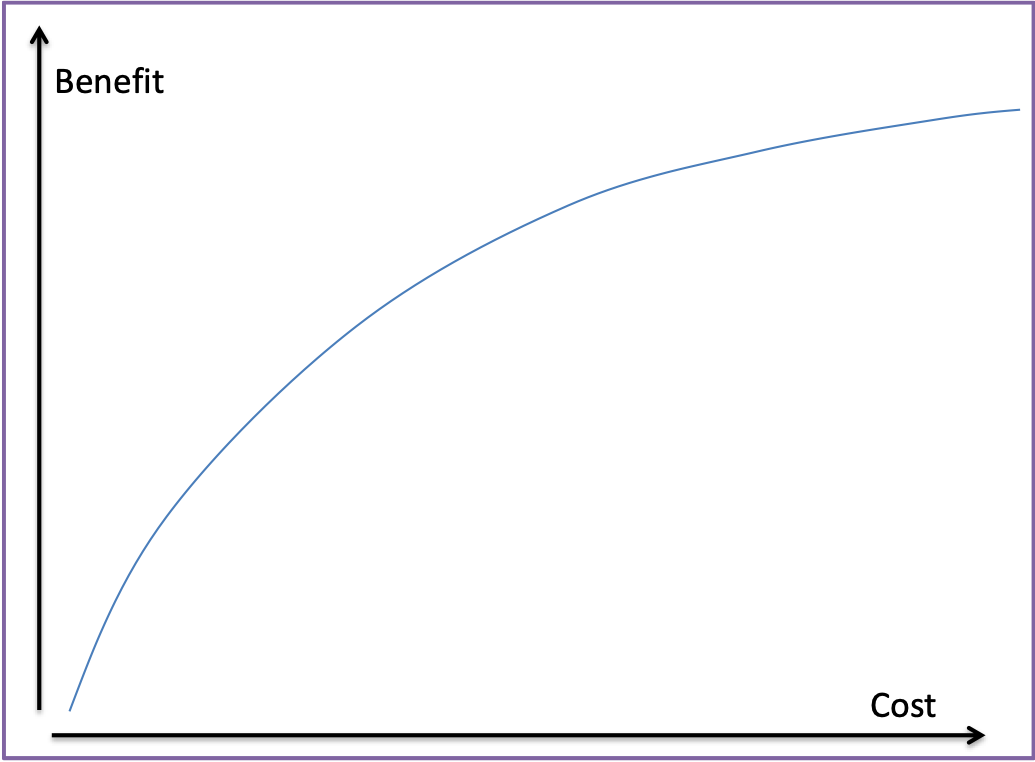

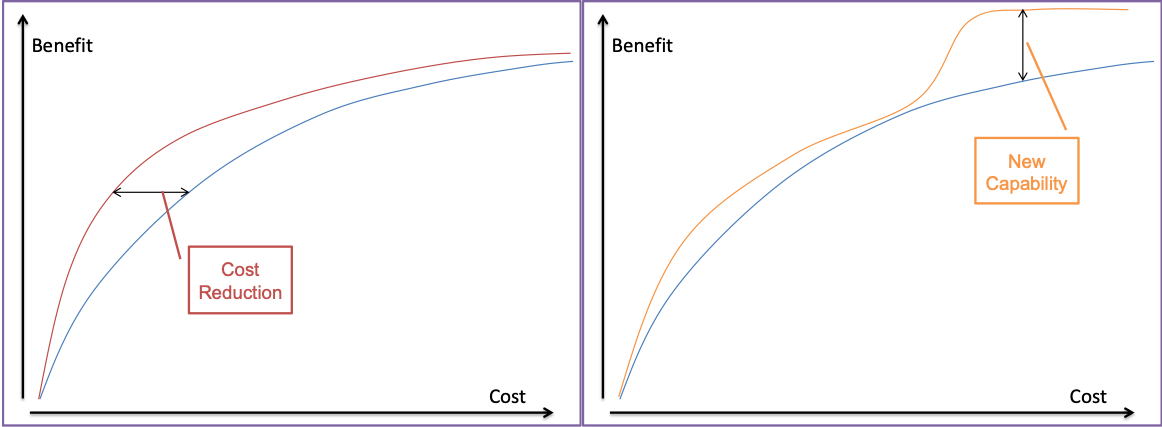

Successful innovation improves your cost/benefit curve in one of two ways, as illustrated below.

The first graph illustrates the cost/benefit curve of a security capability over its lifetime. On one axis, you can measure the money invested (cost) in the capability. On the other axis, you can measure the business benefit of the control. If everything is going well, you should be looking at a curve like this:

The initial implementation of a new security capability usually delivers a strong immediate benefit, but additional investment into existing technologies follows the law of diminishing returns. The business benefit rises over time until it reaches a plateau. When a security capability is operating effectively and efficiently, you exist in a “steady-state.”

Innovation can produce one of two effects.

- It can allow you to reach a steady-state faster by accelerating the ROI, allowing you to achieve the same level of benefit for a lower upfront cost, or

- it can permanently raise the business benefit of the capability, creating a higher level of control effectiveness than could be achieved with existing technology.

Selling Innovation

Since innovation is experimentation, some failures should be expected and welcomed. However, it’s important to make sure that every experiment could succeed and deliver a business benefit.

When considering an innovation experiment, the potential upside should be defined upfront, and you should be able to explain it clearly to any intelligent person using a simple formula.

- “This will help us achieve X faster by accelerating Z.” (cost reduction), or

- “This will help us do X better by solving Y problem.” (enhanced capability)

If you can’t express the benefits of a pilot using this simple formula, it may be a waste of everyone’s time. I encourage you to require even the more junior members of your team to use this language so that everyone is thinking in terms of business benefit rather than playing with cool tech.

Always Fail Upwards

Since innovation is mostly experimentation, and experiments often fail, how do you measure an innovation initiative’s success within your security program?

First, be sure to choose metrics that create the proper incentives. Remember that a failed experiment doesn’t mean a program failure – the incentives should encourage people to try things that might not work. On the other hand, we don’t want all experiments to waste time and resources; incentives should encourage thoughtful and deliberate experimentation. Behavior always aligns with incentives, so get the incentives right as early as possible.

People need time to explore innovations without impacting their regular job. There should be a formal mechanism to support innovation in the InfoSec organization. This mechanism can take the form of “hackathons” or a general policy of dedicating 10% of employees’ time to research and education. Formalizing the program offers another advantage; you can be sure to review ideas for appropriateness and potential business benefit.

Finally, the innovation element is a luxury that not every CISO or DIS can afford at all times. Security innovation may not be a realistic objective if you are the only security person staffing a small security program. Even if you can’t do it yet, you should maintain the goal of formalizing innovation experiments and preparing to implement future-facing capabilities.